DENVER – It’s estimated that in the next 20 years, the United States will invest $2 trillion into the infrastructure of its aging utilities, a former chair of the Colorado Public Utilities Commission told reporters on Wednesday, and it would be wise of utilities to spend that money wisely, on renewable energy resources.

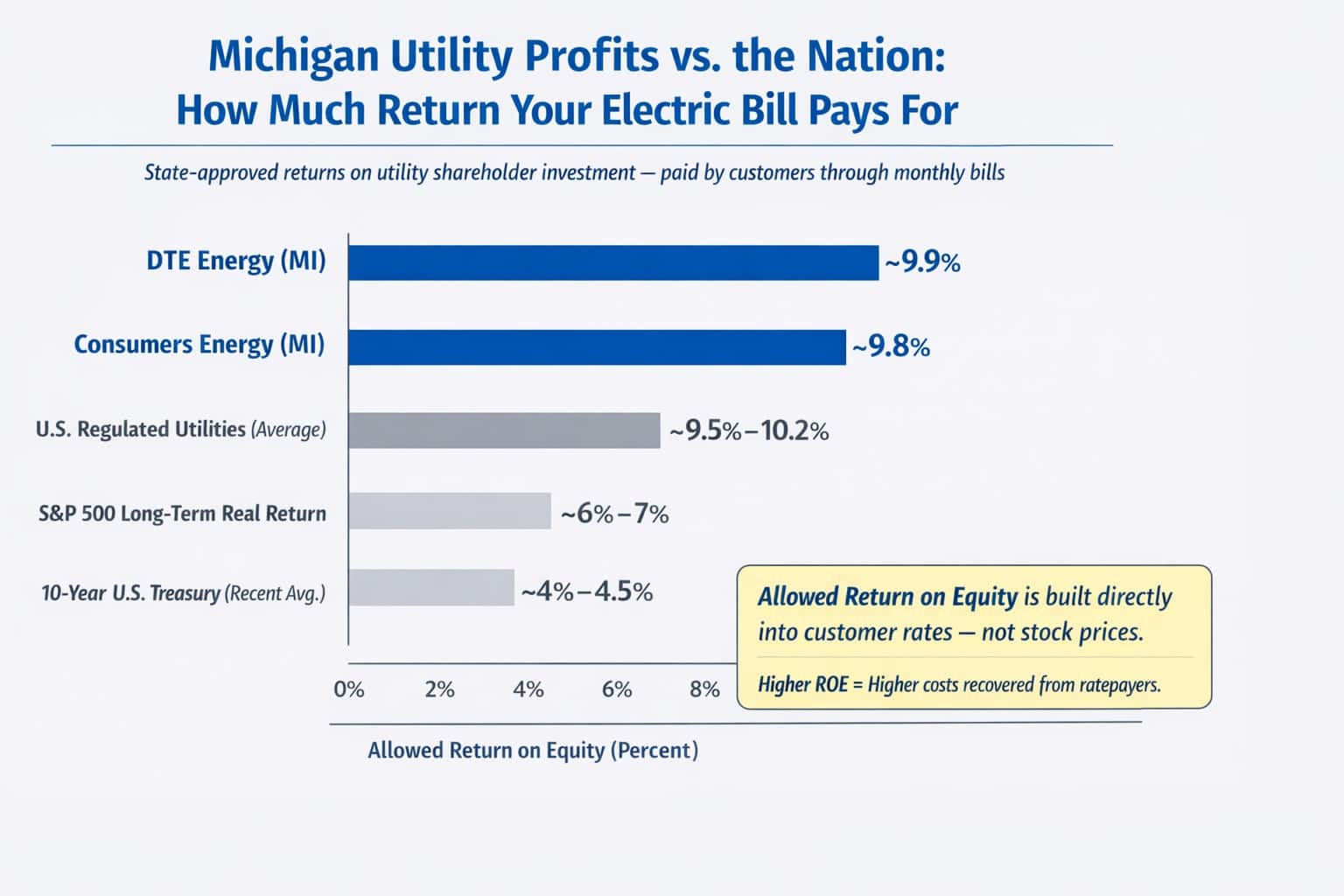

“This will be consumers’ money. It will be funded by consumer rates,” said Ron Binz, now the principal at Public Policy Consultants in Denver, Colorado. “So we think it is incumbent that as a society, but down to the level of regulatory commissions, we accommodate not just the costs but also the risks.”

Between 2002 and 2004, the Colorado Legislature introduced various bills to create a renewable energy standard in the state, but each of them fell apart, Binz said. By 2004, a coalition of environmental groups, consumers groups and agricultural organizations had been able to put a renewable energy standard on the ballot as a voter-initiated law. The successful proposal was 10 percent by 2020.

Michigan’s current ballot proposal is to upgrade the state standard from 10 percent by 2015 to 25 percent by 2025 and would write the standard into the Constitution, which opponents continue to criticize.

“In Colorado, voters did not approve a change in their constitution to mandate renewables, that is a huge difference from what is being tried in Michigan,” Steve Transeth said in a statement.

Transeth is a former Michigan Public Service Commission commissioner turned senior policy adviser for opposition group Clean Affordable Renewable Energy. “Setting energy policy in a state constitution is costly, and will actually impede our ability to meet the challenges that we will face in the years to come. The rosy picture that MEMJ (Michigan Energy Michigan Jobs) is trying to paint doesn’t match up to reality.”

But Binz said that by 2007, the state’s voter-initiated mandate was seen as popular enough by the General Assembly that it passed, on a bipartisan vote, an increase to 20 percent by 2020.

“Three years after that, in 2010, the General Assembly increased it to 30 percent,” Binz said. “I think it was fair to say that the General Assembly recognized the economic benefits to the state that this was bringing, that were manifest: Jobs and industry relocating to Colorado, support services, wind blade manufacturers, solar installers, just across the board. We got a nice bump in economic activity in that sector.”

Binz said that while he could see the argument from the other side about the proposal being in the Constitution, he thought the Michigan proposal is “pretty elegant and simple.” He continued: “It doesn’t mandate a lot of details in the Constitution. The implementation details will rely on what’s in place right now … so there’s a lot of room for creatively implementing this statute in a way that I think will aid in its success.”

Binz did say that he thought the constitutional amendment would make it more difficult to adjust percentage-wise, but that such a point could be moot over the next decade or so of implementation.

Alongside Binz was Dan Mullen, senior manager of electric power programs for the Boston-based nonprofit group Ceres, which Mr. Mullen described as the largest network of business and investor constituencies in North America that looks at how environmental issues affects its members’ investment portfolios.

“Unless commissions and utilities do a really good job of managing the risk of these investments, it’s going to be costly and we could make some costly mistakes. As Ron pointed out, it’s mostly consumers that are at risk here,” Mullen said about spending infrastructure dollars wisely. “But we feel that, especially because the way the demographics work, historically what has happened is as the power sector has invested more and more in their infrastructure, those investments have occurred as usage in society has grown and comparatively that’s actually enabled society to absorb those costs fairly painlessly.”

Mullen said a “tremendous” investment cycle is beginning in the energy sector, especially considering the last time regulated electric utilities played a role in building up its generating facilities came in the 1970s and carried through the 1980s, which he said ended poorly and resulted in hundreds of billions of dollars in losses incurred by customers.

Further, the reality is utility rates will be bound to increase for consumers no matter what, he said.

“Given the fact that rates will be going up, and given the limited tolerance for utility mistakes, we also think that investors are uniquely exposed in this build cycle as well,” Mullen said. “So it’s not only for consumer interest that utilities and regulators need to get this right, it’s also to protect investor interests as well.”

Mullen and Binz referenced an April 2012 report by Ceres that showed, among other things, how traditional energy outlets such as coal and more recently nuclear energy involve much greater financial risks than biomass, solar thermal energy or onshore wind, even though the costs of solar thermal proved to be higher, with or without incentives. Wind, however, maintains both one of the lowest costs and lowest risks, the study showed.

In fact, Binz said, one of Colorado’s largest utilities, Xcel Energy, which originally spent considerable money to oppose a renewable energy standard in 2004, is now one of its fiercest advocates.

“They are today completely supportive of the 30 percent standard, ahead of schedule in making it and their corporate slogan is “Responsible by Nature,” and they rely on their environmental compliance, in particular their wind and solar programs, as a corporate calling card for them now,” Binz said. “So it’s a complete turnaround.”

He added that the state’s other largest energy provider, Black Hills, is also on track to meeting its goals, though it has a much smaller percentage to meet because it is a much smaller company than Xcel.

Binz estimated that Xcel was churning out about 15 percent of its energy from renewable sources and said that the state has lived well within its 2 percent cap on increased costs to consumers. If passed, Michigan companies would have a 1 percent annual cap.

“We used a lot of wind, which was displacing natural gas production. Gas is lower right now, we understand all of that, but that’s an open question about whether or not that’s something you’d take to the bank,” Binz said. “Most economists don’t expect gas prices to stay in the $3 range for a long time. So wind, actually, was lowering the cost of energy in Colorado.”

Admittedly, he said, solar was likely pushing the price up as those resources have seen less interest. But wind could lose its breeze too if the Washington legislators do not extend the federal wind tax credit, known to investors as the production tax credit (PTC). The PTC concern, he said, has caused one of Colorado’s employers to lay off some people until they can assess the demand of wind energy for next year.

However, Binz said the governor during the state’s renewable energy boom, former Governor Bill Ritter, continues to say in speeches that the clean energy sector was the only sector in Colorado that grew during the Great Recession.

“We actually had economic growth and jobs growth in that sector over the period of 2008 to 2011,” Binz said.

To add to that, he said he expects Xcel Energy will go from about a 65 percent coal utility just a few years ago to about 40 percent by the end of 2016, “and probably downward from that,” he said. “Because of all of this, Xcel’s carbon footprint will have been reduced 29 percent by 2005 levels. Rates of residential customers are up less than the rate of inflation, and there’s no tricks in that. These are actual utility rates billed against average number of kilowatt hours per customer.”

This story was provided by Gon