ANN ARBOR – Most new renewable energy projects take the form of massive wind or solar farms. Ann Arbor, Michigan, is trying something different: a new city-owned utility is building a local power network within city limits, made up of solar microgrids and geothermal energy installed at homes and businesses.

“They’re creating a whole new model of energy delivery for a city,” says Mike Shriberg, a professor at University of Michigan’s School for Environment and Sustainability who lives in Ann Arbor, told Fast Company.

The new utility won’t replace the area’s existing power company, DTE Energy. But it will help the city move much faster toward zero-carbon power.

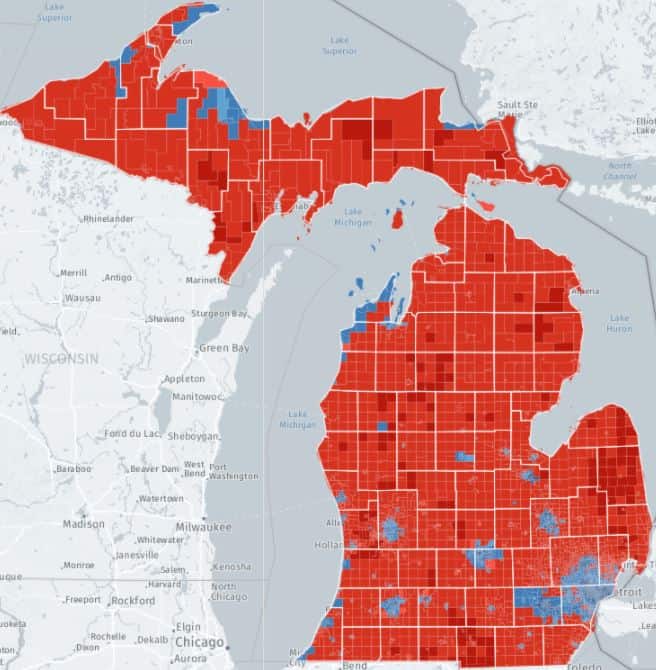

When Ann Arbor—a city of 122,000, with a $550 million dollar annual budget—set a goal to become carbon neutral by 2030, it knew that the electric grid would be a challenge. DTE Energy doesn’t plan to reach 100% clean power until 2050, and the company’s definition of “clean” still includes some fossil gas.

As the city researched options to accelerate the grid’s transition to renewables, it recognized the value of a distributed network with more rooftop solar. But the existing power company wasn’t interested in moving in that direction.

“When we came up with a concept, we reached out to the utility and said, ‘Would you be interested in doing that?,” says Missy Stults, director of sustainability and innovations for the city. “And the answer was no. And our response was, okay, well, then we will.”

The advantage of a local, distributed system

The first advantage of building locally: if power comes from your own roof or your neighbor’s roof instead of traveling long distances, the system is more resilient.

“The most vulnerable part of our energy system is the distribution network— poles and wires,” says Stults. “That’s what a tree falls on and takes out. It’s not generation. So instead of relying on generating our energy in a faraway place that has to move across vulnerable distribution networks, why not focus on generating it in our own community? That’s more resilient. That’s more reliable.”

Building large-scale solar and wind farms is also a long process. Getting permits can take years. The wait to get connected to the grid, called the interconnection queue, can also sometimes take five years or more. The Trump administration is also trying to slow down clean energy even more. And just finding the land can also be difficult.

“We have more and more challenge in finding places to do large-scale,” Stults says. “We need to start thinking about all of the assets we already have.”

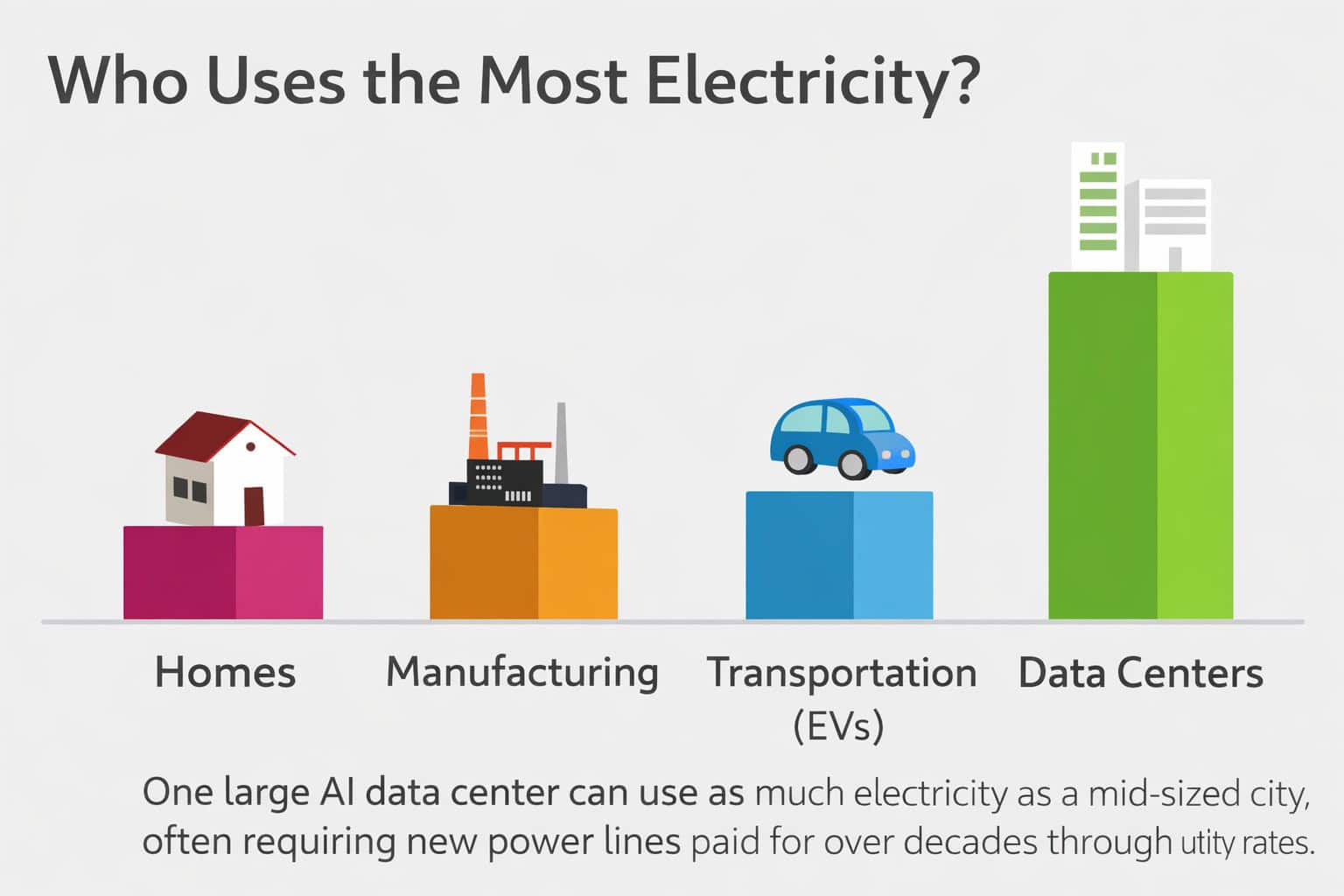

Traditional investor-owned utilities don’t have much incentive to build distributed renewable energy. “They make more money when they build a bigger, centralized power plant,” says Shriberg. Regulated utilities make profits based on a rate of return on their capital investments. “The incentive structure for a city is completely different because you’re looking at sustainability and [consumer] costs and reliability as a driver,” he says.

Of course, trying to scale up solar on tens of thousands of rooftops is also challenging. But because there’s no cost to homeowners—the city will own the solar panels and other equipment—the city already has a long list of residents who want to participate.

A new type of utility

Ann Arbor calls the new system a “sustainable energy utility” or SEU. A few other cities use the same name in different ways—D.C., for example, has a sustainable energy utility that focuses on helping improve efficiency. Ann Arbor will also help residents and businesses become more efficient. But its approach to adding new power generation is new.

The city also considered the idea of a public utility that could fully replace the existing for-profit power company. But that approach would have been slower and more expensive. The city would have had to invest in the utility’s aging, unreliable distribution system.

With the old system, “we have frequent blackouts,” says Shriberg. “It’s a distribution system that’s not working very well. And Ann Arbor determined that they want to build the energy grid of the future. They do not want to acquire the energy grid of the past and then be responsible for maintaining it. So this allows a quick way to do that—to build a new grid and a new system without the responsibilities of maintaining the outdated one.”

Residents will still have access to the old utility, but can sign up to also be part of the sustainable energy utility. The city has calculated that the switch will save residents money on bills.

If someone already has solar panels, they can start selling the power to the new utility and will have the option to let the city add new equipment, like a battery or more panels. (The monthly electric bill for people with battery storage will be higher, but still less than investing in a generator.)

Others can sign up to get solar for the first time. The city will build microgrids in neighborhoods. As more local power is added, it will travel shorter distances—a wire could go from one house to the next. “You would be able to sell to the SEU and it would go literally to your neighbor,” says Stults.

Read the rest of the story at Fast Company